It is often reported that the Great Barrier Reef is half dead, specifically that the corals are bleached, and the water quality is degraded with pesticides and plastics. If I didn’t know better, I might never want to visit a coral reef, lest I be confronted by this reality – apparently all our fault. Except the coral reefs on the way to Myrmidon made me feel so alive. Every day, I dived into crystal clear warm water, to be greeted by little fishes. And I saw a great diversity of different corals. Every day, I wondered if we would make it all the way to Myrmidon –- an ancient and detached coral reef that juts out into the South Pacific Ocean on the eastern edge of the Great Barrier Reef.

I tell this story with Shaun Frichette in the short film Finding Porites –- filmed by Stuart Ireland in 2020.

I have been snorkelling, and more recently Scuba diving, coral reefs for more than fifty years.

In 1970, my family travelled from Cooktown in the far north, down the entire Queensland coast stopping along the way at seaside caravan parks. I missed grade two of school. I got to swim, and to observe nature close-up, and I was allowed to be curious.

I remember swimming in Horseshoe Bay, across the road from the caravan park in the town of Bowen. I still remember the Acropora corals and the parrot fish. Despite claims to the contrary, the same corals and the same fish, are still there, as I show in my first film, Beige Reef –- filmed by Clint Hempsall in 2019.

Through the late 1970s and early 1980s, I snorkelled the coral reefs fringing Sulawesi in Indonesia; first off Pare Pare and later my parents lived in Kendari. Dad bought a sailing boat. Every Sunday we would visit a different coral reef. I wish I had an underwater camera back then.

As a backpacker during university holidays in Australia in the early 1980s, I went to Fitzroy Island, and snorkelled the reefs fringing the southern Whitsunday Islands that are also part of the Great Barrier Reef. Then I spent a period living overseas, including in Madagascar and Kenya where I also got to snorkel coral reefs.

Beginning in 1998, I had the opportunity to work for the Queensland sugar industry and visit farms along important river systems from Mossman to Hervey Bay – as well as visiting inshore corals reefs beyond these river mouths and along the entire Queensland coast.

Beginning in 2006, soon after I started this weblog, I followed the story of an Indonesian coral reef reportedly polluted by gold mining. I travelled to Manado at the tip of the island of Sulawesi to hear the verdict in that court case, and also, to see the corals in Buyat Bay for myself. I wrote a short article about this incident that became the longest criminal trial in Indonesia’s history.

Some ten years ago, from 2009 through until about 2014, I lived at Cooee Bay and snorkelled the reefs fringing Great Keppel Island.

Last year, when I heard that there was mass coral bleaching off Townsville, I visited and found, contrary to international media reports, that the corals were mostly hot pink at John Brewer Reef. The corals had bleached colourful! I’ve been back to that most beautiful coral reef several times since, but so far only the first visit has been turned into a short film, with the colours of those corals shown in Part 1 of Bleached Colourful.

It is the case that for the last 50 years, the doomsayers, have been heralding the imminent collapse of coral reef ecosystems, especially those that are part of the Great Barrier Reef. But they are still there, and as far as I can tell as biodiverse and colourful as ever.

In nature, as in life, we can sometimes find whatever we are looking for and this is especially the case at coral reefs.

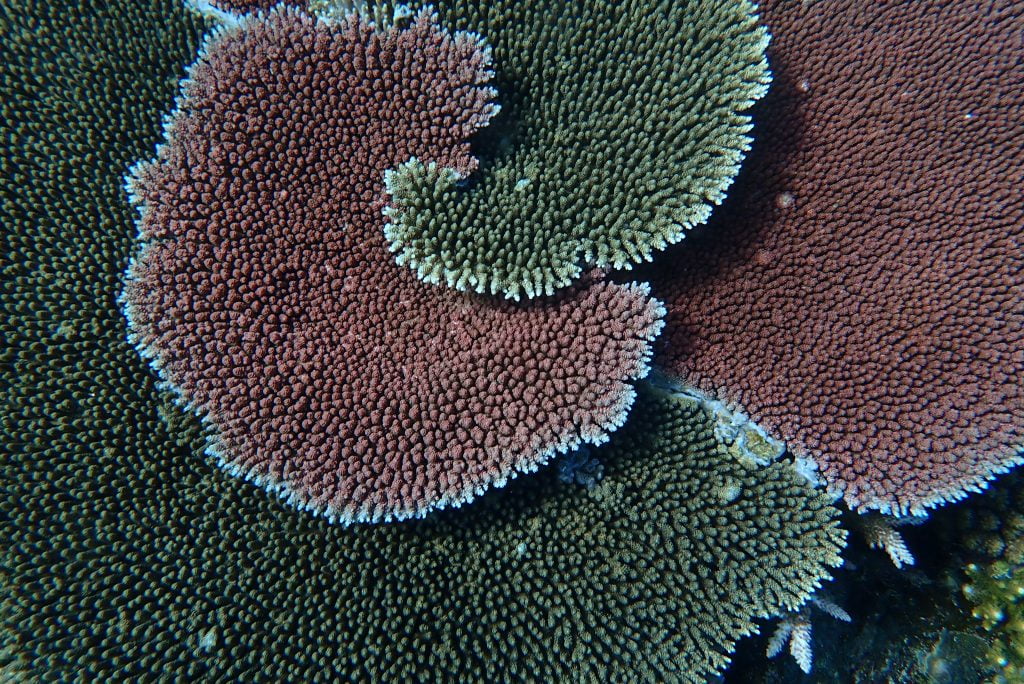

Cyclones and sea level change – especially localised dramatic falls in sea level associated with El Niño events that periodically cause widespread bleaching – will destroy individual coral gardens. And over the edge of reef crests there are always piles of coral rubble. In fact, some of our most mature coral reef systems can grow into flat-topped platforms with live coral only around the perimeter: down the walls. The tops of these ancient reefs may be capped with coralline algae.

I was out some years ago scuba diving at Pixie Reef, just 22 nautical miles to the northeast of Cairns. I went out with two underwater photographers to document Pixie reef for this moment in time. Because despite all the money spent on Great Barrier Reef research over recent decades there is no actual data giving any indication of the true state of its more than 3000 individual coral reefs.

Pixie Reef was classified as badly bleached in 2016, but there are no transect photographs (at least none publicly available) or video giving any idea what this looked like. We just have a score of ‘4’ from Terry Hughes looking out the window of an aeroplane flying at 150 metres altitude.

Can you see me?

I’m floating above Pixie Reef looking at the most beautiful corals, just to the south of the boat – in red bathers.

Much of this photograph shows what looks likes bleached corals, but that is the reef crest and those corals have been dead since sea levels started to fall a couple of thousand years ago! I was looking at the most beautiful corals, while I floated above Pixie Reef, with Stuart filming me from 120 metres above, from a drone.

I’ve put up our transect photographs from Pixie Reef. You can find all 360 photographs here

If I had never visited the Great Barrier Reef, I would be inclined to believe that it was ruined – I could not know otherwise. I would only have the absurd narrative as repeated on the nightly television news. That I have had the opportunity to visit so many reefs, and measure aspects of some of them, must inevitably have a profound effect not just on my political outlook but also my state of mind.

Jennifer Marohasy

March 2023

Postscript

I’m beginning a program of study that considers coral reef health from three different perspectives: coral colour, percentage cover, and also coral species biodiversity. I’m also interested in the oldest Porites and would like to begin an inventory of them, I’ve already named my largest so far Porites Craig.

It is relatively common to find healthy Porites around 2-3 metres in diameter, but it is rare to find them as large as Porites Craig (8.6 metres in width), it is also rare to find Porites that have been bleached dead. I’ve found them both (large, healthy and bleached, dead) at Pixie Reef (22 nautical miles to the north east of Cairns).

Aerial surveys of coral bleaching by Terry Hughes from James Cook University have been published in prestigious journals, and have made media headlines around the world as showing the Great Barrier Reef to be 60% dead, with implications for local tourism, the regulation of agriculture, and the operation of coal mines.

If I had never visited the Great Barrier Reef, I would be inclined to believe him, and that the reef is ruin. As it turns out, I know that Professor Hughes has a methodology that is consistent while misleading.

Professor Hughes looks out the window of aeroplanes from more than 120 metres altitude and variously scores his perception of the corals below. It is actually impossible to know the state of corals from this high altitude. The reef crest at Britomart, for example, looked desolate from a 120 metre drone aerial on 30th November 2020, when in reality it had live coral cover. But I could only know this by getting in, and under the water.

Following is a list of the coral reefs that I surveyed in November and December 2020, with Pixie Reef recently surveyed for a second time in February 2021. The aerial photographs show how little is visible from 120 metres above these coral reefs. The underwater photographic and video transects give an indication of species diversity and coral cover.

This is just the beginning. The plan is to survey more reefs. I would like enough transects to be able to draw statistically significant conclusions about coral cover and species diversity including by habitat type.

In order to understand species diversity it will be necessary to make species lists, and this necessitates an ability to identify key taxa. This requires close-up photographs from under the water. And so I have the beginnings of a page with information about the more common coral species.

It is a fact that the Great Barrier Reef is a thin veneer of living coral growing over layers of dead coral. At many reefs the dead coral is more than 20 metres thick.

Various research reports would suggest that the Great Barrier Reef is not growing as well now, as it was 4000 years ago, during the Holocene High Stand when it was hotter. So much perhaps depends on where we are in particular climate cycles, whether that be the 18.6 year lunar declination cycle, or the Milankovich cycles. Did you know, for example, that sea levels were 120 metres lower than they are now during the depth of the last ice age that was 16000 years ago?

Surveys by the Australian Institute of Marine Science suggesting that since at least 1985 live coral cover has never been more than 25%. It is unclear what percentage of this coral regularly bleaches. There is evidence of bleaching back 3000 years, but little information on changes in the severity or frequency over the last few hundred years.

There are various government-funded surveys of corals at the Great Barrier Reef, including programs run by the Australian Institute of Marine Sciences and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. These are in addition to the regular fly-overs surveying for coral bleaching by James Cook University. While extensive in scope, none of these programs actually provide publicly accessible evidence/archived data for their conclusions about the state of particular reef, nor do they appear to distinguish between the different habitat types at individual reefs when making claims about coral cover.

The program of work through Reef Check Australia apparently lost significant government funding after reporting no general deterioration in coral cover for the period 2001 to 2014.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD is a critical thinker with expertise in the scientific method.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD is a critical thinker with expertise in the scientific method.