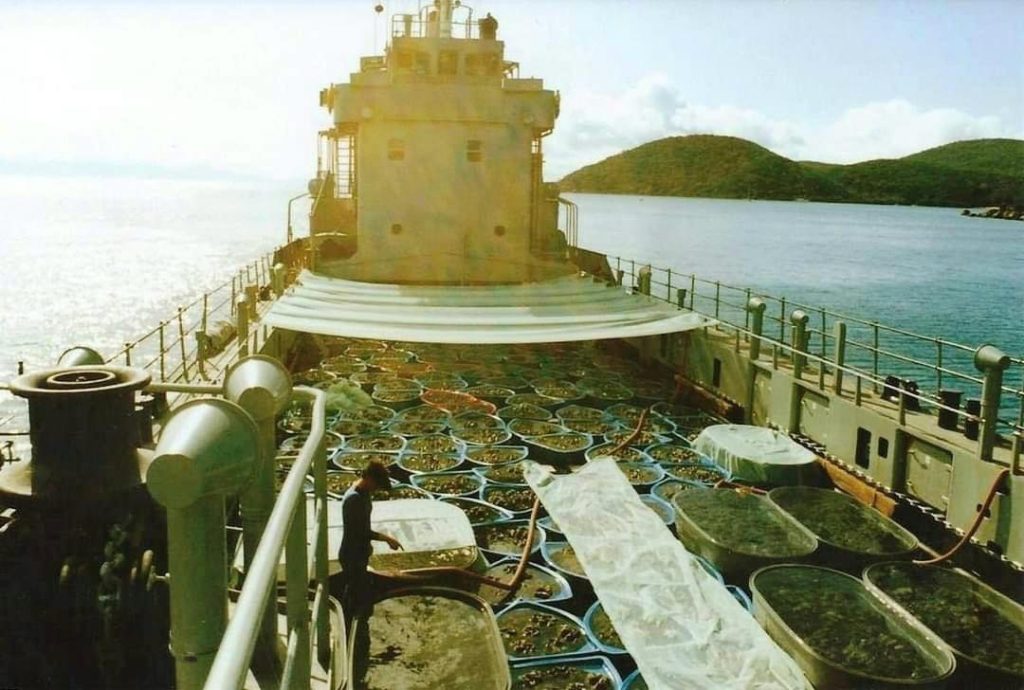

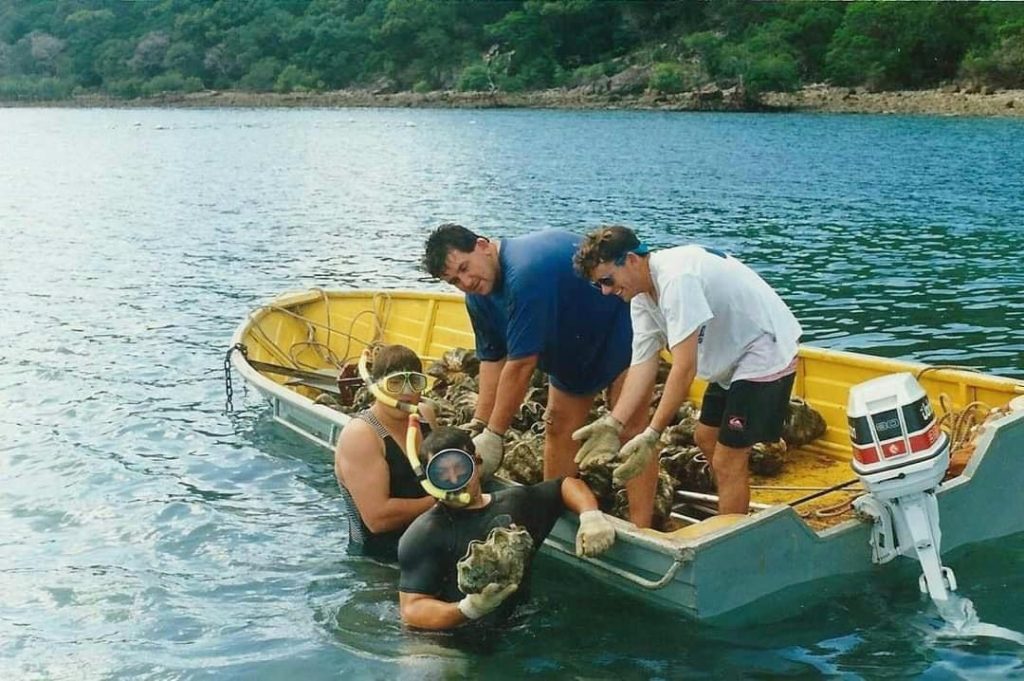

In May 1992, and again in March and April 1993, the Royal Australian Navy, specifically HMAS Tarakan, was involved in the translocation of tens of thousands of clams as part of Operation CLAMSAVER. The clams were moved from a successful breeding program at Orpheus Island to various locations on the Great Barrier Reef, including to Grub Reef.

I am grateful to Jon Daly for providing me some photographs from that time.

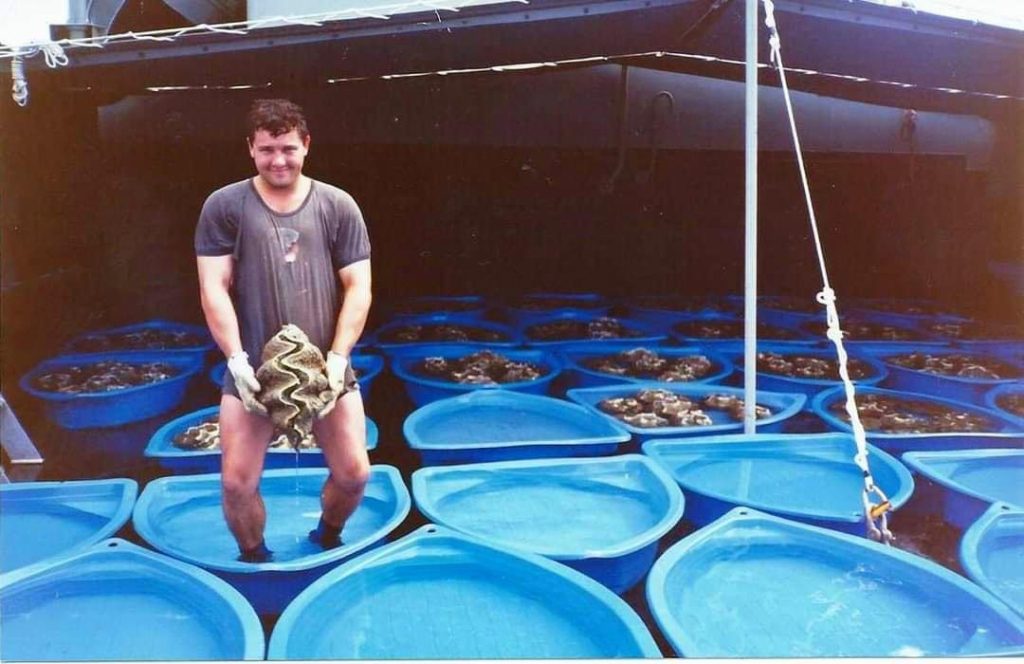

Daly wrote: “The guy in the top image is Paul Livermore … photograph of Tarakans tank deck covered in plastic scallop shaped children’s paddling pools a continuous spray from the ship’s fire main … I’m in the blue t-shirt. [end quotes]. And I have more notes from other conversation with Jon Daly, for another time.

There appears to have been little if any follow-up, to know the fate of the clams.

Considering the photographic evidence from Jon Daly, the clams were not much more than30cm in length when they were moved. How big are they now?

As part of the inaugural Megafauna Expedition – with the charter of the MV Sea Esta funded by Sydney-based philanthropist Simon Fenwick – we set off for Grub Reef on Wednesday, 4th September.

The skipper, Paul Crocombe, did some careful research and reconnaissance in advance of the expedition and was able to find one of the translocation sites.

Despite the blustery conditions, strong surface current and the ever-present risk of colliding with a one of the many bombies, Paul got the MV Sea Esta safely into Grub Reef and the team close to one of the translocation sites.

Good job!

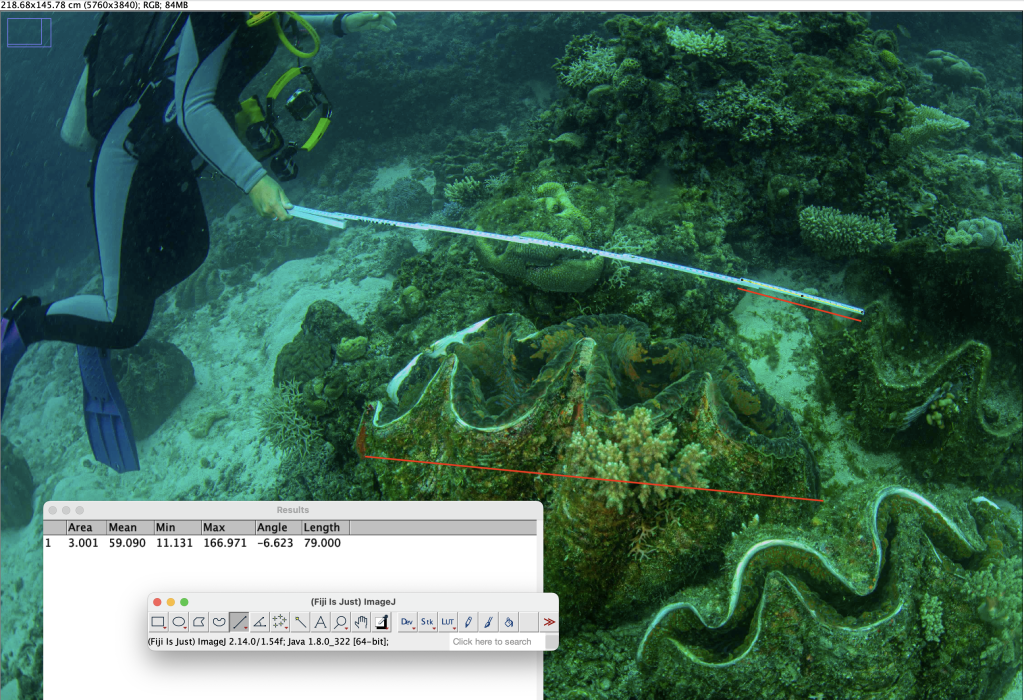

Underwater photographer Jenn Mayes with her scuba buddy Nadine Huth found and photographed the largest clam at 1.47 metres. Congratulations!

And so, the winning photograph in the expedition’s photographic category ‘largest clam’ is by Jenn Mayes and shows Nadine Huth holding the metre long ruler across one of the clams saved by the Royal Australian Navy.

The same clam is shown in the feature photograph at the very top of this blog post.

To be clear, this is one of the clams saved by the Royal Australian Navy as part of operation CLAMSAVER.

There is so much more to tell, about that day at Grub Reef and how it unfolded, even a whale shark encounter for Dave Armstrong.

Rick Braley, who was involved in the original translocation effort, asked that we measure some clams, and that was not only done by the photographers with their yardsticks, but the underwater team also had a tape measure. The mean length of the clams measured on the first dive with the tape measure was 1.11 metres (n=6), and on the second dive was 0.91 (n=8).

And Jenn Mayes found more than clams at Grub Reef, even a slipper lobster on the night dive, filmed by Stuart Ireland.

UPDATE

Paul Livermore and others from the Navy who were involved in operation Clamsaver have been in touch following my related social media post. And so, I have more historic photograph, for a future blog post. Paul Livermore is so pleased to know that their baby clams are now all grown up. The relevant Facebook post is pinned to the top of my official Facebook page, ’tis here: https://www.facebook.com/JenniferMarohasyOfficialPage/

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD is a critical thinker with expertise in the scientific method.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD is a critical thinker with expertise in the scientific method.

Onthe half shell with a beer !

The only credible explanation I can find for the “endangered species” designation is human harvesting – overexploitation – and hence the initial secrecy about location of their destination.

Were all species designated, were specimens of all species included in the breeding programme and subsequent re-distribution?

All the sources quoted in a Google search name climate change as their primary threat. May we now declare that this is another claim debunked by actual evidence from the sea floor?

In the 80s, all nature films ended with a narration on how humans are the ‘greatest threat’ to these animals – and then mentioned a project to protect them. Now, it’s not humans but ‘climate change’.

But whatever it is, we need conservationism from the local people.

I am Dr Rick Braley and was the JCU organiser for t he translocation of the giant clams from Orpheus Island to the two sites at Grub Reee fn May 1992. See my pages on giant clams on my website at https://www.aquasearch.net.au/giant-clams

There are some photos of the 1992 translocation with the mv Tatrakan and some of one of the sites taken by me in 2018. Note there are a lot of dead shells in the 2018 photos. I berllieve those mortaliteis would have occured due to cyclones (Yasi for exdample). Broken spears from Acropora would have rrained down from the shallow reef strucutre above to the deeper sandy area below where theclamswere located. Any Acropora spear that cut into the soft mantle tissue of the clams would eventially kill them.

The second site at Grubwas donethe following day but to date thete has not yet been fre-located.It has a special memory for me as I could have died there. The sun was going down on a calm sea. The last two singgy loads of clams were finising up. I was watching which clamds being thrown over boared landed cvorrectly from my spot neat to the engine when I was suddendly hit in the head with a clam thrown over byone of the sailers. Iwas urshed to the boat bleeding profusely. We steamed to Palm Isalnd and zhad about 9 stitches and a piece of my skul boae chipped off. 50 cm from the wound was thesuiture of the skull boast. I knew that the work was draining and we had to work fast so I forgave thesailer who throew he clam ashewas likleytrying to throw it over me but beig tierd theanded on my head.

IAcouple of mmenrts on other peoples’ comments . Yes, people have been the causeof the demnise of the largest species of giant clam in virtually all former countires of it sdistributiion, except fortheGBR,where natural populations are still found. However, climate change will have incrasingly negative effect on natural populations becauseof the loweriing of pH. Whilel a more acid environment may notaffect existing adult clams (and other bivalves) it will have serious effects forthe larval stage when fir5st shells are developed in the veliger stage. Mortality willl incraese under a more aciid ocean and we are unlikley to ever see hihgh density natual populations as crrently exist on the GBR. See my paperin Mossuscan Research published June 2023 entitled A population study of giant clams (Fam. Tridacninae) over three decades on the /great Barrier Reef.

Great to see them grown up!

The striking thing about this species, the largest of all the giant clams, is how rarely the juveniles are found, and almost never are they abundant. Why has there been no sign of recruitment of young clams downcurrent of the many thousands still left in the bay near the research station on Orpheus Island? They release hundreds of millions of eggs at a time, and being so close together in the bay, egg fertilisation rates should be high.

Survival rates of the eggs and larvae must be almost zero. With such low recruitment rates to the adult populations, fishing is effectively a mining operation. Almost any level of fishing pressure is unsustainable.

So I think fishing pressure is a more imminent threat to this species than climate change.

The fossil record is composed of mostly extinct creatures. Only the snails have longevity.