In March 2025, much of Queensland was lashed, drenched and then drown by torrential rains with downpours of 180 mm in a single day, breaking records for March, swelling rivers and flooding plains. From Burketown to Winton to Adavale to Thargomindah, graziers have been isolation and suffered tremendous losses, yet their resilience shines through. The water is now moving slowly to Lake Eyre, there will also be renewal.

As I comment on the deluge and the Bureau’s failure to forecast it—from the equatorial Pacific Ocean to Lake Ayre overland—I hold those still affected close, wishing them strength amid the heartache.

Where did this water come from? It began as water vapor over the western Pacific’s equatorial zone, a warm ocean expanse near Indonesia where sea temperatures above 28°C fuel intense evaporation. Think tropical convection and hot towers—cumulonimbus clouds with tremendous updrafts—drawing columns of water from the warm ocean’s surface to the very top of the troposphere.

The monsoon trough lingered at the wet season’s tail, moving this moisture inland, dumping it across Queensland’s Channel Country. Some, like Simon Turton, argue this wasn’t just La Niña but a warming world amplifying the water cycle, delivering what fell in Winton and Adavale. More likely the Bureau needs not only better tools for forecasting drought and flood cycles, but also to be monitoring volcanic eruptions in Indonesia that can seed the atmosphere with condensation nuclei.

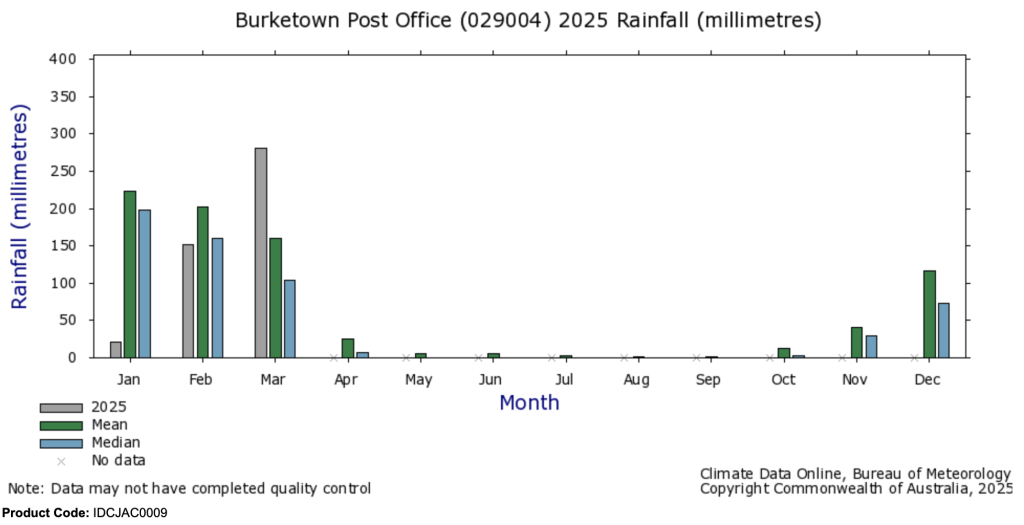

The Bureau of Meteorology’s autumn forecast, released February 27, 2025, painted a misleading picture: warmer-than-average temperatures across Australia, with rainfall “likely to be in the typical range” and “drier than usual for most of Queensland” outside southern and southeast areas. Tropical lows and monsoon bursts were noted as possibilities, but few expected the scale of what unfolded. Western Queensland, pegged for below-average rain, instead saw its third-wettest March since 1900, with 207 mm statewide—124% above the 1961–1990 average. Winton recorded daily falls of 120–180 mm, breaking records from 1910, while Adavale’s Bulloo River surged, evacuating its 30 residents. The Bureau’s models missed the mark, underscoring a need for them to move to better tools.

In August 2011, John Abbot and I visited the Bureau of Meteorology keen to share output from our rainfall forecasting model built using commercially available AI on a laptop computer to forecast monthly rainfall. Meanwhile the Bureau are still producing hopeless forecasts using an expense to run, and expense, super computer costing hundreds of millions of dollars. We wanted to work with the BOM suggesting artificial intelligence (AI) had great capacity for more skilful seasonal forecasts.

Oscar Alves, then the head of their long-range forecasting unit, did not dispute that our AI-based model was generating more reliable monthly forecast for 17 Queensland locations, up to 3 months in advance, but that because the climate, he claimed, was on a new trajectory, our method would not work for many more years.

Oscar Alves’s boss, Andrew Johnson, the current head of the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, also seems to understand very little about natural climate cycles and the application of AI. Johnson is a Malcolm Turnbull appointee. Back in 2011, John Abbot and I were affiliated with Central Queensland University and funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.

There are now many studies in applied mathematics and AI, already published in the scientific literature including by myself and John Abbot showing the potential application of AI for rainfall forecasting. Some of this technology is beginning to be adopted in Asia, including in Indonesia where I was part of a program with the Indonesian Bureau of Meteorology (BMKG). The first paper that Abbot and I got published was by the Chinese Academy of Science. They are leaving Australia behind, for sure.

Since 2018, our work on monthly rainfall forecasting has been continued mostly by John Abbot, click here.

I quit mostly because of the extraordinary backlash when John Abbot and I began extending our rainfall forecasting work to climate change. Gavin Schmidt at NASA and others ran a campaign against us, not by way of coherent criticisms in the scientific literature, but as attacks on Twitter wanting the retraction of an article we had just got published. You can read my comprehensive defence of that article at climatelab.com.au, click here.

Oscar Alves and Andrew Johnson continue to fail to recognise that the world’s climate is always changing; there are cycles of different frequencies some spanning hundreds, others span thousands, even millions of years. Most importantly they can be described mathematically and forecast using AI, but it requires a new way of thinking. Even think tank employees often fail to understand that the climate has been changing, even before woolly mammoths, which are, I am told, the third-most depicted animal in ice age art, after horses and bison. Some of these people, running the institutions, would prefer to discuss ice age art than the application of AI to rainfall forecasting. Consequently, because those in charge mostly don’t seem to care, the little people, Australians attempting to earn an income independently of government suffer. When was it that Johnson before a Senate Committee claims surprise that anyone took the Bureau’s forecasts seriously.

A friend recently emailed me, awed by how this water vapour, unseen in the sky, became a flood of such magnitude. “A few days before,” he wrote, “it was just floating around until temperature and saturation made it fall to earth.” His point captures the wonder: the atmosphere holds vast reservoirs—billions of tonnes of vapour yet we only notice when it falls.

In western Queensland this last March, that falling was relentless, driven by low-pressure systems likely nudged by Rossby waves and volcanic eruptions, soaking already saturated soils. Rivers including the Georgina, Diamantina, and Cooper Creek have overflowed, submerging roads and homes drowning livestock, much of this flooding now continuing in slow-motion.

The water is on the move, heading west to Lake Eyre, Australia’s lowest point at 17 meters below sea level. The Diamantina River’s waters are already trickles into Lake Eyre North’s Warburton Groove. The main flood pulse, from Winton and Adavale, crawls through the Channel Country at 1 km/h, spreading over an area five times the size of the United Kingdom.

The prediction is the waters will reach Lake Eyre by late April, peaking from June to August, potentially rivalling fills from 2009–2011, though not 1974’s full basin flood. Evaporation and floodplains will claim much, but enough may linger to draw pelicans and tourists by winter.

For western Queensland, these rains were a paradox—life-giving yet also heartbreaking for many. Graziers welcomed dam refills, but not drown livestock and supplies. Adavale’s evacuation and Winton’s record-breaking deluge test endurance. To those still cut off, checking livestock through mud and awaiting road repairs, we see your struggle. Your stories—of neighbours helping neighbours, of facing this flooding cycle with grit—inspire us.

We care deeply and hope for brighter days as waters recede.

For individuals and communities rebuilding, the challenge is immense, yet the same water promises renewal at Lake Eyre—a rare spectacle of this land’s natural climate cycles.

May those affected by the flooding rains find strength to match the rivers’ flow and may we all carry more respect for the forces shaping our world the endless cycles of destruction and rebirth.

*******

Key technical papers detailing my method for monthly rainfall forecasting are listed at the Climatelab.com.au website, click here.

For Lake Eyre updates, to watch the water flow in, click in.

Bureau of Meteorology’s 2025 Autumn Long-Range Forecast

27/02/2025

The Bureau of Meteorology has released its long-range forecast for autumn 2025.

While autumn is often a time for cooler weather to begin, this season is very likely to be warmer than average across Australia and summer heat may persist into early autumn.

Rainfall is likely to be in the typical range for the season for most of Australia…

It’s also likely to be drier than usual for most of Queensland except for southern and south-east areas.

Tropical cyclones, tropical lows, storms and active monsoon bursts are still possible in the north over the coming months, which can bring particularly heavy rain.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD is a critical thinker with expertise in the scientific method.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD is a critical thinker with expertise in the scientific method.

A great article Jennifer, love your thoughts on Climate and excited to see them taken seriously.

Thank you Jennifer for another interesting article.

I agree with Michael. You’re a legend Jennifer!

Great work. I love your research and articles. Thx

It’s called Climate Change… get used to it.

Yes Karen

Ever since the planet was formed and long B4 we’d evolved….

Why aren’t volcanic atmospheric anomalies factored in?

Cloud seeding is a thing, so we know Sulfur and other particles affect weather when they reach altitude, but they seem to not be a contributing factor in modelling.

Krakatoa was a major event and had a major impact on climate for atheist two years after the event.

Is it just that the IPPC, want an easier target?

Jennifer,

In this post, you put a link to an earlier post titled “The Future of Climate Forecasting (Part 1)”

Is there going to be a Part 2?

Thanks Jen, for a great summary. As someone who has lived in the Sturt’s Stony Desert and Diamantina region I can only say from experience that these big wets happen every couple of decades or so, usually when least expected.

In some places providing water as extensive as 80 k that the flying doctor won’t fly over.

The song says “the rain never falls on the dusty Diamantina” but it does occasionally.

And it rains fish, too.

Hasn’t tourism been banned from Lake Eyre?