I was privileged to have the opportunity to study science at university, and I have always been particularly interested in taxonomy that is naming, defining and classifying groups of organisms based on shared characteristics. This is fundamental to knowing the distribution and abundance of animal species, and how this might change, for example, following severe coral bleaching.

Early in my career I was a field biologist in Madagascar. After three years I was moved to Nairobi, the capital of Kenya, and from there I travelled all over Africa collecting plants and pressing them, but mostly species of insect, which after killing, pining and drying if it was an adult, or pickling if it was an immature, I would post the specimens to experts at the British Museum in London or the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC. That was back in the 1980s, for seven fantastic years.

Good work boots are important for this type of outdoor work, as was a foldable magnifying glass. So often, being able to count, for example, the number of spatulas on the third instar larvae*, was important to know whether a specimen was worth collecting, or not. It is much the same in marine biology. I am learning that, for example, accurately counting the number of tentacles on a polyp is the easiest way to distinguish a hard coral from a soft coral.

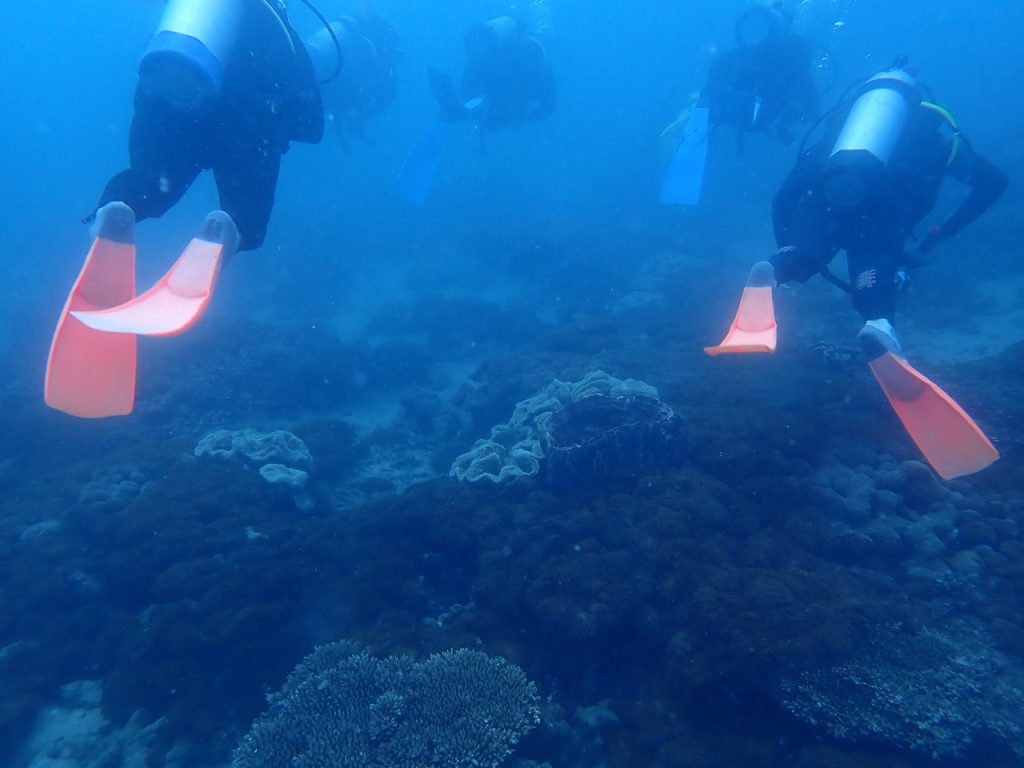

Of course, fundamental to current climate science politics is knowing the percentage hard coral cover at the Great Barrier Reef. It is quoted everywhere from UNESCO reports to Peter Ridd’s YouTube videos. I worry though that those doing the counting in the field may not be provided with the most basic instruments for getting this right, and then there is the importance of having a specimen lodged somewhere of each species, or at least a photograph. If the overall percentage, and how it is trending, is to be at all accurate it must begin with a reliable identification.

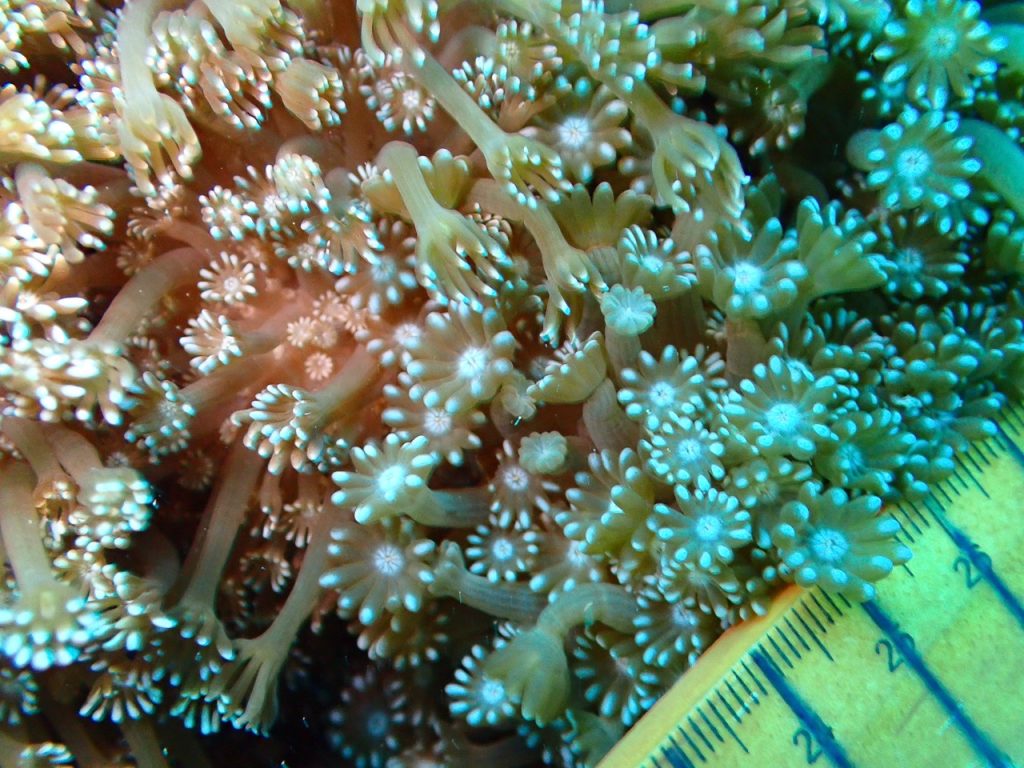

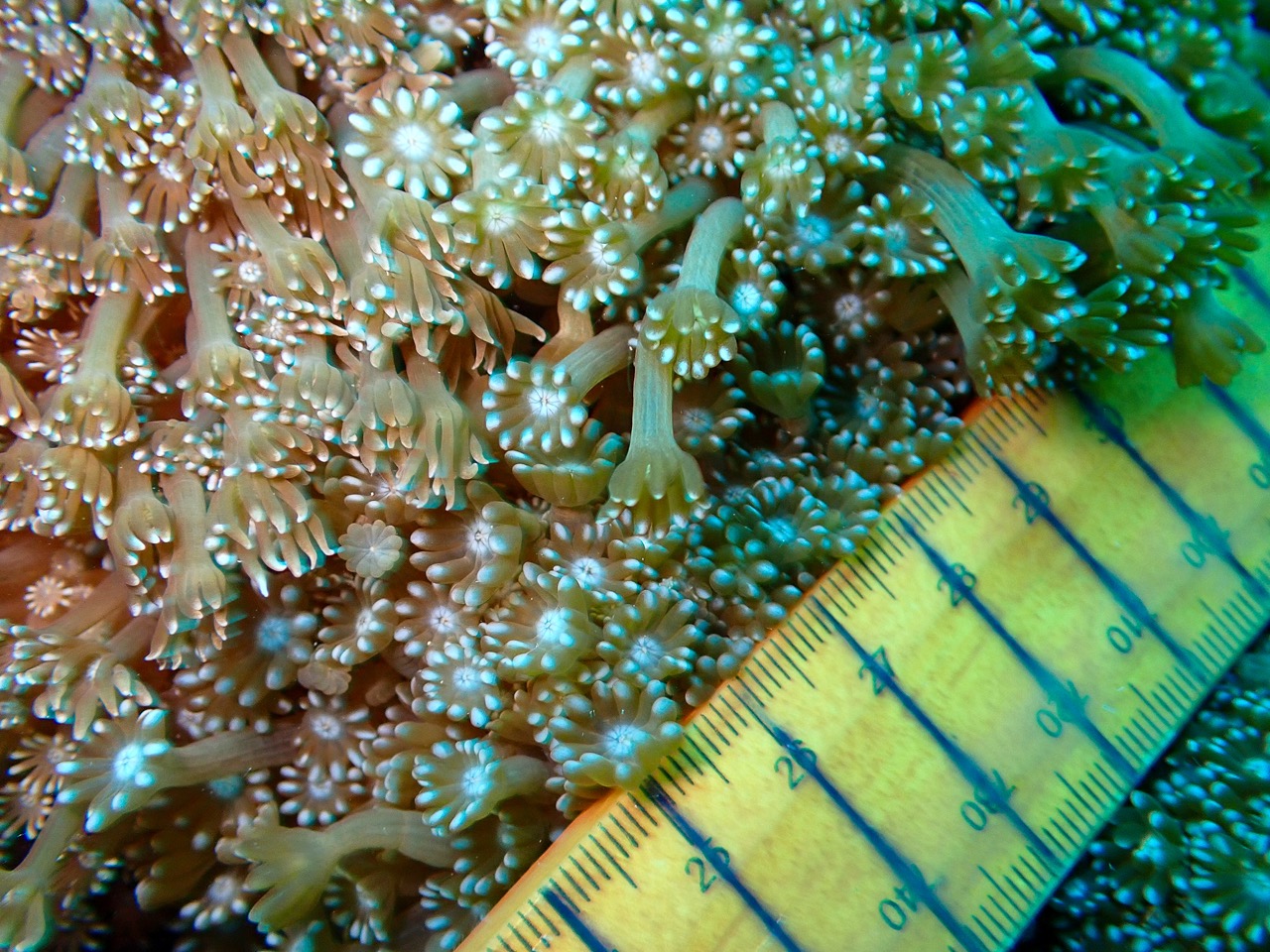

In the textbook about classifying soft corals by Katharina Fabricius and Philip Alderslade, they explain that hard corals in the genus Goniopora and Alveopora are often mistaken for soft corals, when the hard exoskeleton of calcium carbonate is invisible under a thick layer of expanded polyps. In fact, it is critical to count the tentacles on the polyps: soft corals have 8 tentacles, Gonipora have 24 tentacles and Alveopora 12. Given the polyps of many of these species are only a few millimetres in diameter it is impossible to know how many tentacles exist without a form of magnification.

I use my Olympus TG6 underwater camera, as I once used a magnifying glass. It can provide magnification up to 44 times, which is rather a lot.

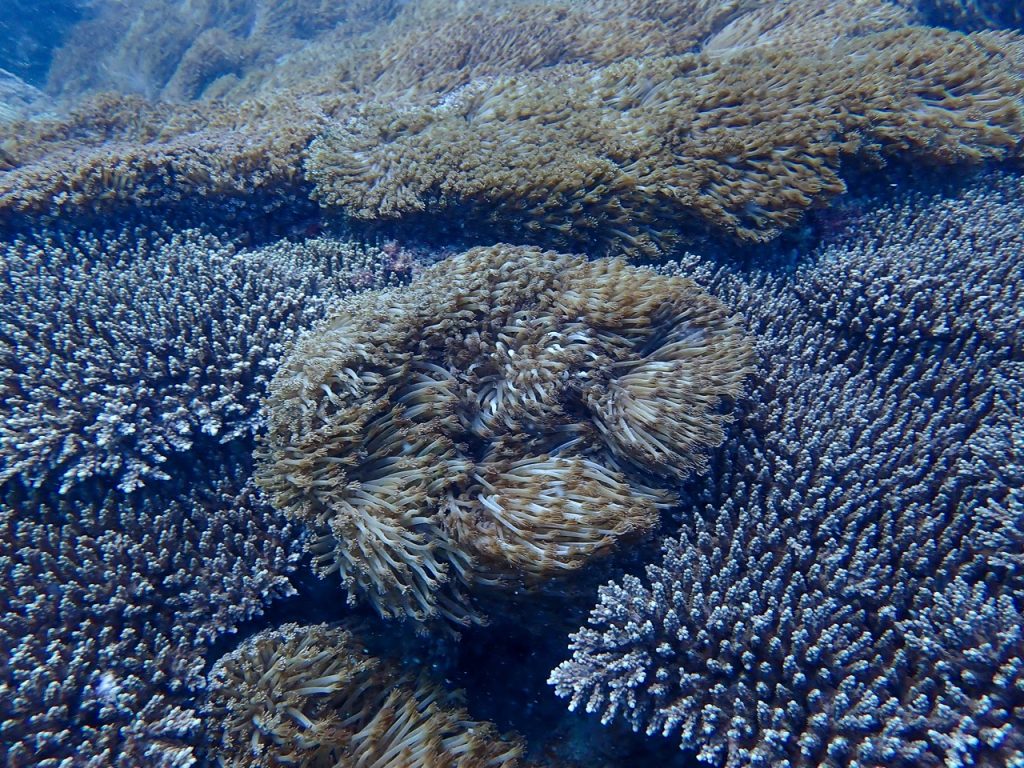

What happened underwater at the Keppel Island reefs this last year is that first, all the corals bleached a stark white. That was reported in the New York Times in March, I was first able to photograph this in April. Then many of the dominant branching hard corals – the Acropora – they began to die.

These branching Acropora became infested with what are called macroalgae. It was like these corals became covered in a light green moss. That attracted what are called the grazing herbivores – algae eating fish including oh so colourful surgeon fishes. Of course, with all the little fishes getting fat grazing the macroalgae, soon there were schools of fish-eating fish including yellow-tailed barracuda; that grew bigger and bigger.

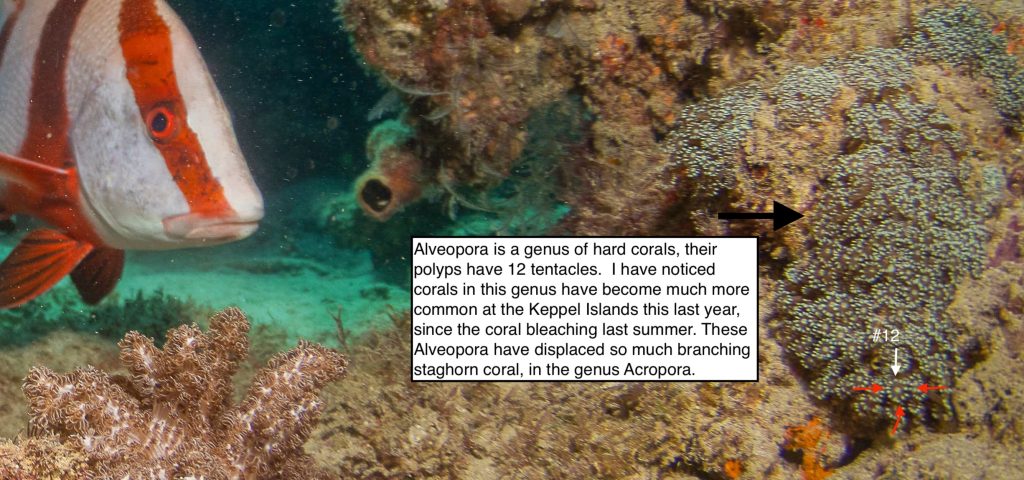

But what has fascinated me most was not the abundance of fish, but the displacing of the fields of Acropora with Alveopora. As the branching Acropora disintegrated the Alveopora took hold. This was most noticeable at Bald Rocks reef because of the barrel sponges. They used to be surrounded by tall branching Acropora, now they are quite exposed with the structurally less complex and rather short Alveopora.

To be continued.

*Classification is fundamental to having a shared language for communicating changes in the distribution and abundance of plant and animal species, especially in the biological sciences. Having a binocular microscope was often important; for being able to know one species of plant or insect from another. By counting the number and knowing the shape, for example, of the spatula on the third instar larvae of a particular species of fly – I was able to describe 28 new species of plant-feeding gall midge from different species of acacia when I lived in Kenya. I didn’t do it by myself, I worked with Raymond J. Gagne at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington D.C.

Postscript.

I was going to keep this photograph by Jenn Mayes from Wreck Beach reef over for another blog post, but it is too much fun to not keep sharing, this time with a focus on the Alveopora.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD is a critical thinker with expertise in the scientific method.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD is a critical thinker with expertise in the scientific method.

Thank you, Jennifer for your very thoughtful post. Your history of working in Africa, and the explanations of taxonomy you applied there, and now at Keppel Island, are fascinating.

I look forward to reading your continuing narrative. I have great admiration for your work.

The implications of the observations you present about corals are tantalizing. It will be interesting to see where this goes. The glimpses of the field biology work you did in the past are fascinating.

Thank you for both.

I would have thought a fly larva would have just one spatula. But regarding the rest of your post, I think, like any ecosystem, coral reefs need a diversity of coral species.

By the way, you might find it interesting that questions regarding the accuracy of the temperature record are not going away

https://open.substack.com/pub/peterhalligan/p/just-like-the-us-the-uk-simply-makes?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=1b15yf

It’s not a conspiracy.

https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/learn-about/how-forecasts-are-made/observations/obs-critical-for-weather–climate

Thanks Jen, One learns something everyday. I have seen corals in different places -the GBR, Sabai, Fiji, Vanuata etc (even at Bass Point NSW- shown to me by my daughter who is a Marine Biologist). However, I have not thought about the many different types of hard and soft corals. One certainly would not be able to get information of what is on a reef or in the inter-tidal areas by flying over. Keep up the good work.