“ALL five global temperature estimates presently show an overall stagnation, at least since 2002. There has been no increase in global air temperature since 1998, which however was affected by the oceanographic El Niño event. This stagnation does not exclude the possibility that global temperatures will begin to increase again later. On the other hand, it also remain (sic) a possibility that Earth just now is passing a temperature peak, and that global temperatures will begin to decrease during the coming years. Time will show which of these two possibilities is correct.”

That’s according to Ole Humlum, Professor of Physical Geography, University of Oslo, writing in his latest monthly Climate4You Update.

While Professor Humlum is confident we will be able to see the cooling trend once it establishes. I’m increasingly of the opinion that with the algorithms now used to systematically adjust the thermometer temperature record, any cooling will be increasingly obscured in the global temperature record. Of relevance, none of the global temperature records have been stable over time. Two of the global surface air temperature records, National Climatic Data Center and Goddard Institute for Space Studies, show apparent systematic changes creating an administrative upsurge in temperatures. The difference between January 1915 and January 2000 temperatures was 0.39 degree C in 2008, it is now 0.52 degree C in the direction of warming. This is illustrated on page 7 of the June 2014 Climate4Your Update.

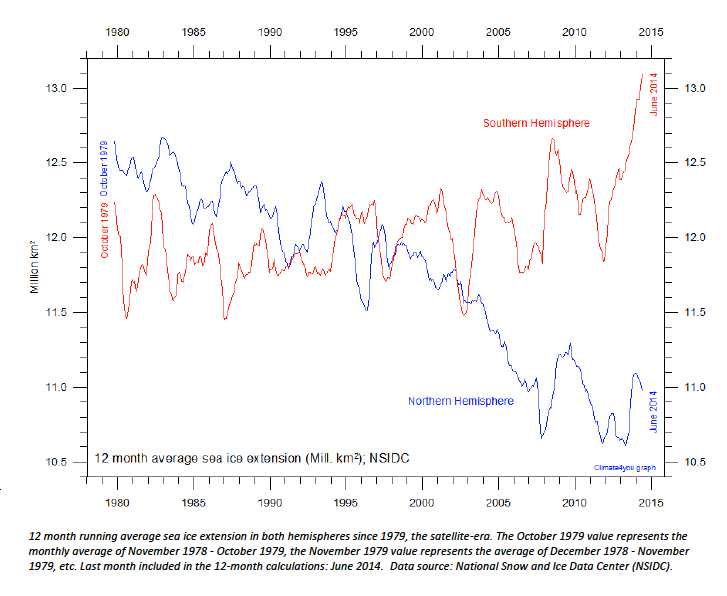

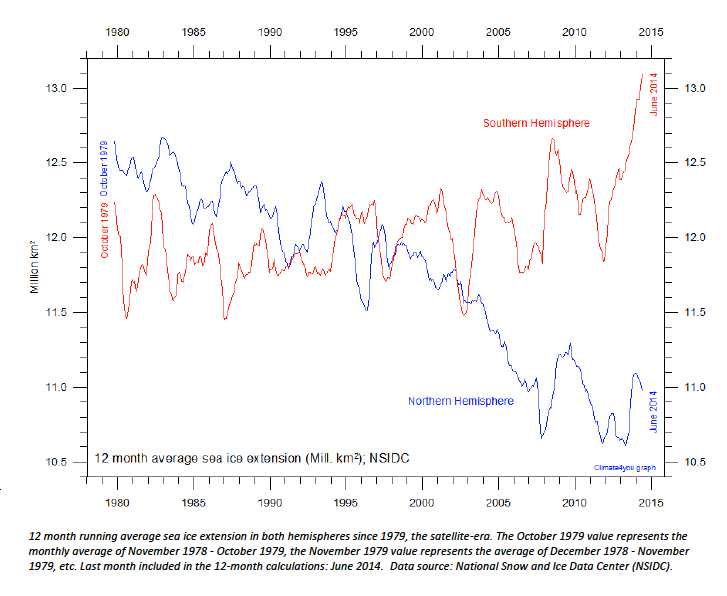

The most relevant chart in the latest update from Professor Humlum for Australians, particularly Murray Darling farmers, is perhaps the 12-month running average sea ice extensions in both hemispheres since 1979, page 24 and reproduced below. According to Kevin Long, a Bendigo-based long-range weather forecaster, higher sea ice averages in the Antarctic signal below average rainfall for eastern Australia and heavier late season frosts.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD is a critical thinker with expertise in the scientific method.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD is a critical thinker with expertise in the scientific method.

I’d hate to break it to Kevin but we have had plenty of late season frosts in the last decade. Late October in 2013. Cloudiness is the most important inhibitor of frost North or West of the Divide. Clear sky, no wind and you get frost until daytime temps exceed 20c.