Bramble Cay is the northern most island at the Great Barrier Reef. It is officially the site of the first mammalian extinction directly attributable to climate change, the Bramble Cay melomys.

The rat was declared extinct by the Australian Environment Minister in 2019 on the basis it can no longer be found on this small coral island that is Bramble Cay.

The late Rob McCulloch had a different hypothesis, that this tiny island never sustained the original population of this rodent, rather the rat periodically arrives on driftwood from New Guinea when the Fly River floods. He hypothesised that the rat still exists in New Guinea.

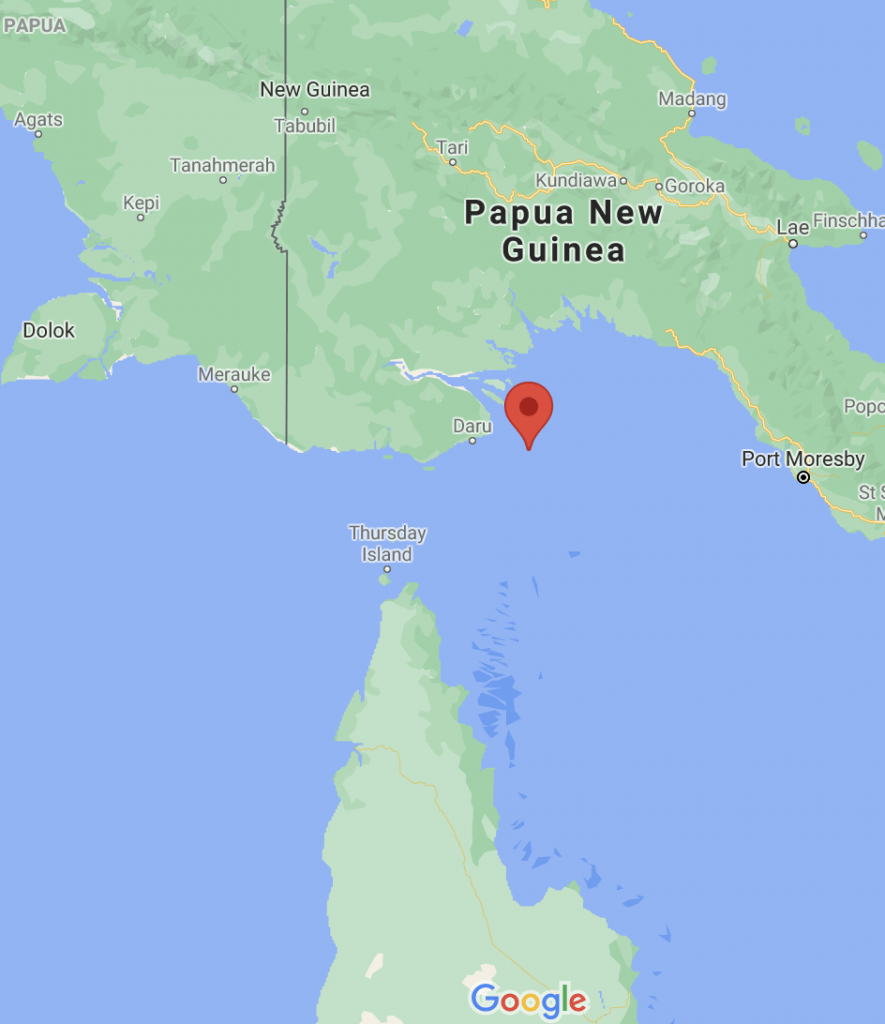

Bramble Cay is only 27 kms from the delta of the Fly River that is one of the largest rivers in the world by volume without a single dam in its catchment.

I would be keen to go looking for the rat, first at Bramble Cay, and also to head across and search the islands at the delta of the Fly.

The delta of the Fly River is over 100 km wide at its entrance, but only 11 km wide at the apex upstream of Kiwai Island. The delta contains 3 main distributary channels 5 to 15m in depth, separated by islands that are stabilised by mangroves. Three of the largest islands, Kiwai, Wabuda and Domori, are inhabited.

The climate change hypothesis

The rat’s extinction has been blamed specifically on inundation from storm surges, and also rising sea level. It is worth considering that while an increase in the incidence of severe storms is claimed to have caused habitat loss resulting in the extinction of the Bramble Cay melomys, the very formation of such coral cays is dependent on storms/cyclones. Specifically storms/cyclones smash corals, aggregate it, and then throw-up the coral rubble beyond the highest tides.

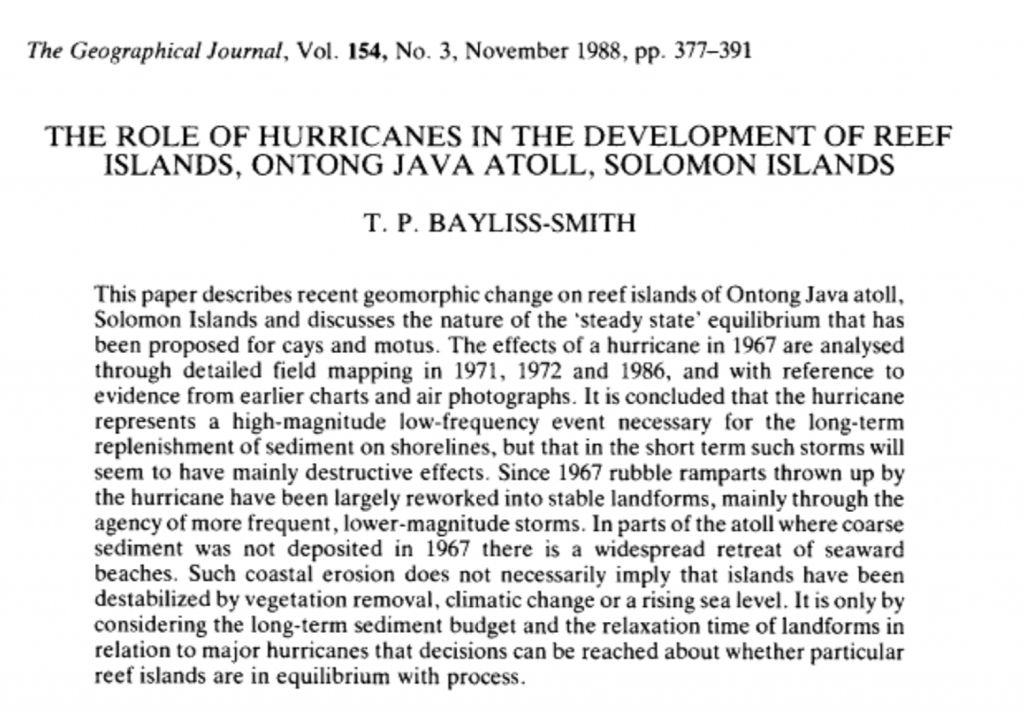

Cyclones are also necessary for the long-term replenishment of sediments along such shorelines, as explained in an article by T.P. Byliss-Smith (The Geographical Journal, 1988). This must especially be the case for coral cays if there has been an increase in global sea levels over recent decades.

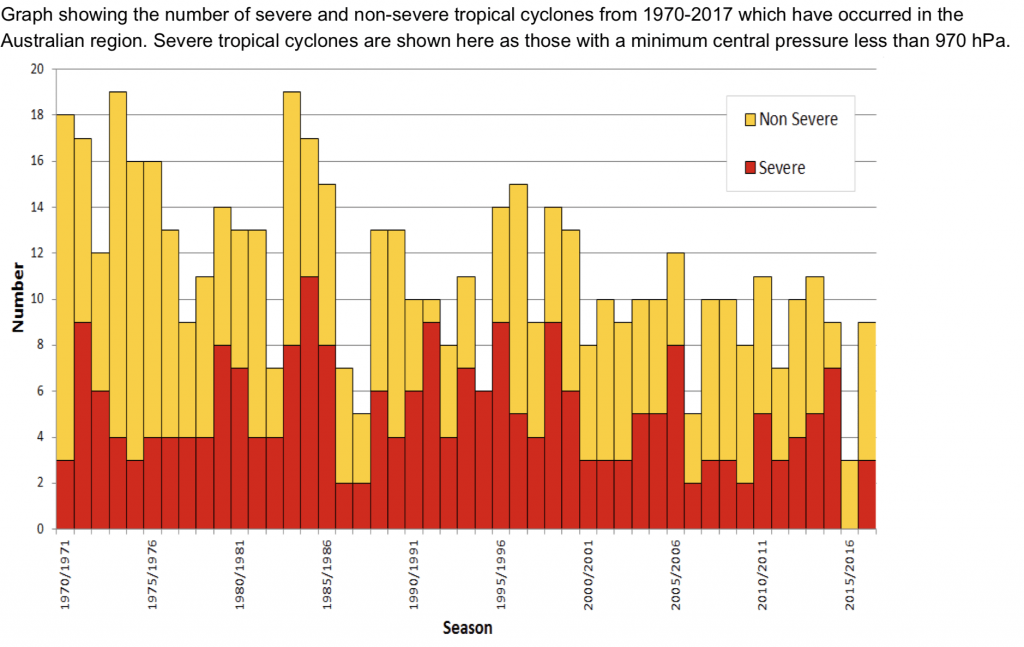

Interestingly, according to The Australian Bureau of Meteorology neither the frequency nor intensity of cyclones is increasing.

More information on tropical cyclone trends can be found in advice from the Bureau of Meteorology, click here.

While meteorologist Greg Browning acknowledged on 13th October 2020 that ‘recent decades have seen a decline in the number of tropical cyclones in our region.’ He predicted that the 2020-2021 cyclone season would buck this trend, though this did not prove to be the case. This last season again saw a decline in the number of cyclones crossing the Australian coastline.

An Alternative Working Hypothesis

Bramble Cay is only 27 kms from the delta of the Fly River that is the largest river in the world by volume without a single dam in its catchment.

During period of flooding, rats may be washed from rainforest understory along the Fly River, arrive at Bramble Cay, multiple in numbers for a period (particularly when there is an abundance of turtle eggs), but the Bramble Cay population will always be susceptible to extinction because the island is so small. When a habitat lacks complexity and refugees it is always more vulnerable to extinction from predation by birds and/or snakes that can be intense.

Is it possible that there could be cycles of migration (from the highlands of New Guinea), extinction (due to predation) and then recolonisation (with the next significant flood event)?

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD is a critical thinker with expertise in the scientific method.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD is a critical thinker with expertise in the scientific method.